Blog Posts | January 24, 2017

Share ThisBy Dr. Sharon Strover

University of Texas at Austin

With just a little over 2,000 people in western Kansas’ Stanton County, you might be surprised there’s a library in the area. But the Stanton County Public Library is heavily used. If you went there after hours and looked on its outdoor patio, you might see people at the Anna Mae Lewis Outdoor Library using the Internet connectivity from the library’s network.

As our team visited rural libraries in Kansas and Maine, we routinely saw parking lots and streets filled with patrons using Wi-Fi connections after hours. Our IMLS grant project, led by investigators Sharon Strover (University of Texas at Austin), Brian Whitacre (Oklahoma State University) and Colin Rhinesmith (Simmons University), is supporting research on the information ecosystem of rural regions, seeking to understand the role of libraries and programs such as loaned hotspots.

By some estimates, there are 4,078 rural libraries in the U.S. and they’re important in more ways than you might expect. Going well beyond book lending, rural libraries support all sorts of educational programs, maker spaces, and social service meetings. They also have public access computers and most provide Wi-Fi accessibility both inside and outside their buildings.

We have been visiting many of them over the past several months as part of an effort to understand the relationship between rural libraries, broadband access and how people get information. In many rural areas, quality, affordable home Internet access is tough to come by. So what do people do? They go to the library. In Maine, this may mean using the library’s fast 100 Mbps network connection, provided by the Maine School & Library network (MSLN). In Kansas and Texas, as in other states, people go to the closest spot that has a decent Internet connection in order to file some paperwork or to check in on some friends or relatives or to work on something else. National statistics repeatedly show that people in rural regions use the Internet less often and have fewer home-based connections, but the research does not often dive into the problems associated with a poor-quality connection or how people compensate.

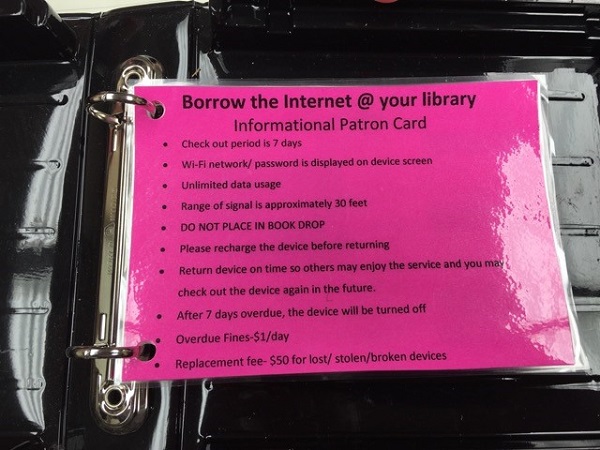

Library hotspot lending programs can begin to address some of the problems people face in both urban areas (where affordability is the biggest problem) as well as rural regions (where both access and affordability may be issues). While New York Public Library’s program is the biggest, NYPL also generously partnered with the Maine and Kansas library systems to make a few hundred hotspots available to rural libraries in those states. We asked librarians in those two states what people are doing with them.

First off, in some locations the hotspots are so popular there are waiting lists. Educators check them out to use on school field trips so a busload of students can get mobile access. Home-schooling families use hotspots in Maine and Kansas to retrieve lesson plans and to network with other home schoolers. In addition, some community organizations use them. For example, 4-H volunteers in Goodland County checked out hotspots to process credit cards at the County Fair. The high school used the hotspots to register reunion attendees. A hunting organization used the hotspot connection to register members during its convention. One family used a device to ensure their son could finish his schoolwork while visiting a sick relative. One librarian told us that many patrons used the devices at home to seek jobs.

Rural libraries serve as trusted public institutions in small towns all over the country. While many people seem to think libraries only loan books, in fact, rural libraries are critical local information institutions in their communities, providing spaces and resources for many community functions, from social services to citizenship to early childhood education, to children’s reading skills. Lending hotspots extends the library into people’s homes (and other places), and even makes libraries’ electronic resources more available to patrons.

Are hotspot programs a sustainable solution for rural Internet? Right now, these programs depend on special funding, often from foundations or benefactors, and arrangements with mobile phone companies providing connectivity. That connection might have a data limit, or maybe the speed will throttle at a certain point. Even if the library is a public institution and provides free services, the hotspot itself is still privately provided and the connectivity is not free.

Library hotspot lending programs may provide a highly useful function for rural populations but several things have to fall into place to ensure they can make a meaningful contribution to the community. One critical question concerns whether these systems can keep up with the bandwidth demands of the types of applications people need the most, and what libraries’ roles might be–or should be–in rural community information environments.

We have another year of research ahead of us and look forward to sharing our results with libraries and other constituencies interested in the vitality of rural areas.

About the Author

Dr. Sharon Strover is the Philip G. Warner Regents Professor in Communication and former Chair of the Radio-TV-Film Department at the University of Texas, where she teaches communications and telecommunications courses and directs the Technology and Information Policy Institute.