Grant Spotlight | May 1, 2008

Share This |

Recipient: Grant: Pictured: |

Web site: |

||

Twelve-year-old students across the country are digging into the secrets of ancient Mesopotamia through a teaching Web site that lets them direct virtual archeological expeditions and curate museum exhibits with the excavated artifacts. The Web site, Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History, examines gifts left to the modern world of the region that includes Iraq. It was developed by the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute Museum in partnership with Chicago Public School teachers, the University of Chicago’s Chicago Web Docent, and the eCUIP Digital Library Project and was funded by a National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

"We needed to bring Mesopotamia out of the textbook and into the virtual world in order to grab kids’ attention," said Wendy Ennes, project director and Teacher Services and e-Learning Coordinator at the Oriental Institute Museum. Most sixth graders nationwide are required to study ancient civilizations, and the Web site was built to appeal to and support different learning styles – online interactions, reading and visual exploration, as well as searching and browsing strategies.

Students who enjoy gaming love Dig Into History in the Interactives section of the Web site, where they lead digs in present-day Iraq to collect and catalog Mesopotamian artifacts. Students select a quest statement that relates to a big idea about ancient Mesopotamia such as the beginning of writing, the development of certain inventions, or the domestication of plants and animals. Students then dig for artifacts in an early village, a city on the plains, or an imperial capital. Meanwhile, the "dig leader" must solve problems such as sand storm delays, drooping team morale, and funding issues. Students must discover at least four artifacts that support their quest statement, catalog their characteristics, write labels, and craft an overarching statement. Their work culminates in the students curating an online museum exhibit.

"By collecting and curating a museum exhibit, kids learn how exhibits are structured and what a curator’s job is like." Ennes explained. The interactive section also includes video interviews with three archeologists and detailed analyses of 13 artifacts.

The site offers three other sections: Life In Mesopotamia, which presents details on 14 topics surrounding daily life in ancient Mesopotamia; Teaching Materials with 16 lesson plans, which synchronize with the National Council for the Social Studies Curriculum Standards; and the Learning Collection of 142 artifacts and photographs of archeological sites.

The topics covered in Life in Mesopotamia drive home one of the Web site’s central themes: that ancient Mesopotamians and their myriad gifts still affect almost every aspect of our daily lives 5,000 years later. Among those gifts are:

-

- Writing: The Sumerians developed one of the earliest writing systems in about 3,200 B.C.

- Mathematics: Symbols for numbers were found on the earliest written documents.

- Time: The Mesopotamians were the first to divide time units into 60 parts, leading to the 60-second minute and 60-minute hour.

- Urban civilization: One of the world’s earliest cities was Uruk, which by the year 3,000 B.C. had an estimated population of 50,000.

- The wheel: The ancient Mesopotamians were using the wheel by about 3,500 B.C. They used the potter’s wheel to throw pots and wheels on carts to transport people and goods.

- The sail: The Mesopotamians made sails to harness the wind to move boats.

- Astronomy: From a very early time, the Mesopotamians had charted the movements of the sun, moon, planets, and stars and were able to predict celestial events.

In addition, the Teaching Materials section includes a Symbols From History (PDF, 97 KB) assignment that asks students to research the use of ancient symbols in modern Iraq using newspaper articles, library visits, and the Internet. As students learn about the ancient past, they also become more aware of current events in Iraq.

"With all that is going on in the world today, it is important that American students know and appreciate the legacies that we have inherited from this region of the world," Ennes said.

The Learning Collection allows kids to "zoomify" in on photos of artifacts and examine them up close. "Students like looking at the cracks because the cracks tell them that an artifact is really old," said Ennes, noting that the section also provides opportunities for visual analysis, discussion questions to get classroom conversations rolling, links to related artifacts, and maps pinpointing where the objects were discovered.

For teachers who wish to learn more about Mesopotamia and earn graduate credit, the museum offers an in-depth, eight-week Online Professional Development Course. The online course is now being disseminated in publications and conferences so that K-12 teachers nationwide can benefit from the museum’s offerings.

Ennes and the museum staff learned many lessons as they developed this rich resource. For example, they learned that organizing metadata and digitizing collections takes a very long time.

"This was our first attempt to digitize and make public a portion of our collection. These particular artifacts came out of the ground between the early 1900s and the 1950s, and the metadata didn’t exist in a manageable form. We had to gather a lot of old archival information located in card catalogs, Institute publications, and from other places throughout the Oriental Institute and museum. There was a lot of research done for each object. It also took a lot of time to photograph and digitize the artifacts," she said. Museum prep staff developed a portable backdrop and a mobile studio so that Ennes could shoot the artifacts in situ when the museum was closed. In addition to writing the grant and shooting the photos, Ennes also wrote much of the content for the site – particularly for the Dig Into History interactive.

Staffing issues cropped up during the project: the museum lost its museum director and the Web site’s Flash developer. Fortunately, Geoff Emberling, the new museum director, threw his support behind the project. eCUIP’s original programmer, Glen Biggus, and Web designer Steven Lane collaborated with Sean York, Chicago Web Docent’s Flash developer who had moved across the country, to develop a template that helped streamline the programming process for Dig Into History.

"All museum departments had to support the project for it to succeed," Ennes said. "As an institution we had to find the time to collaborate on the project and meet challenges we faced along the way. Now that we know what it takes, we can look forward to tackling a larger digitization of our collection in the future. We’re better prepared for what’s involved," Ennes said. "It was a labor of love and I’m happy it’s out there. We couldn’t have done it without IMLS’s support."

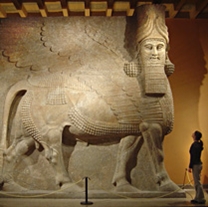

About the image: Lamassu, 721 BC - 705 BC, Oriental Institute Museum #A7369.

This colossal stone sculpture (weighing approximately 40 tons) was one of a pair that guarded the entrance to the throne room of King Sargon II's palace at Dur-Sharrukin (modern-day Khorsabad, Iraq). A protective spirit known as a lamassu, it is shown as a composite being with the head of a human, the body and ears of a bull, and the wings of a bird. When viewed from the side, the creature appears to be walking; when viewed from the front, to be standing still. Thus it is actually represented with five, rather than four, legs.

Photography by Wendy Ennes, courtesy of the Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago.