Grant Spotlight | April 1, 2006

Share This |

Recipient: Wildlife Conservation Society/Central Park Zoo, New York, NY |

Project Partner: |

||

"A culture is no better than its woods."

W.H. Auden from Woods

(England, 1907-1973)

(on display as part of a poetry installation at the Central Park Zoo)

Need

Zoos are continually looking for ways to better communicate with their public. The conservation message, a core theme for most accredited American zoos, is a challenge to present quickly and effectively. The Central Park Zoo, an innovator in interpretive concepts for zoos, has turned to poetry in its quest to portray the significance of the earth’s loss of biodiversity.

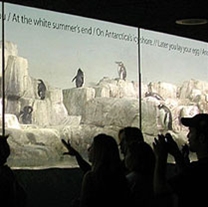

The Wildlife Conservation Society, which runs the city’s aquarium and zoos, partnered with the Poets House, a national literary center with a 45,000-volume poetry collection, to establish a poet residency at the Central Park Zoo. A first-of-a-kind, the project resulted in the placement of 41 poems and excerpts in a variety of places alongside the animal exhibits.

The poems are nestled in gardens, sprinkled across park benches, tucked among the open-air rafters. Just as the animals do, they delight those who catch a glimpse, who pause to absorb their beauty.

Goals

The zoo’s interpretive signs must present complex information about animal species, habitats, and histories while simultaneously describing the survival struggles of endangered species. It was thought that poetry, on the other hand, could communicate the conservation messages in more expedient ways.

Poetry could give an emotional wallop to the zoo’s conservation themes, making points powerfully and, in some cases, with very few words. The idea was for the poetry to complement—but not compete with—the messages the zoo already works hard to present. The zoo felt that poetry could be the gateway for voices from both near and far that have valued wildlife and conservation during the course of human history.

For Poets House, the project held the promise of creating a very visible presence for poetry. It was an opportunity to show the relevancy and beauty of the art form to the one million visitors who would bump into the poetry each year.

To reach a variety of audiences, project participants had a goal to provide a selection of works representing different parts of the world, different centuries (some dating back 27 centuries), and even different rhythms. The poems could be about a specific animal on display at the zoo, but more often would speak to a general conservation theme.

The zoo project planners had a sense that the project could be a powerful way to increase visitor awareness of conservation issues, but planned to test the project’s true effectiveness with a scientific study.

Strategy

The Poets House had an important front-end role to assist with project planning and with the selection of a poet who would be an experienced researcher, an accomplished poet, and someone deeply steeped in conservation thinking. That someone was San Diego State University professor and Montana resident Sandra Alcosser, an award-winning writer, the poet-laureate of Montana, and former poet-in-residence at two national parks. She had been one of the distinguished poets invited to serve on the project’s literary panel to assist with the project, and had stood out among the applicants who had responded to the project’s open invitation to poets nationwide. Today, Alcosser remains the poet-in-residence at the Central Park Zoo.

Ms. Alcosser sifted through thousands of potential poems, while spending time with zoo biologists and the zoo’s director, Dr. Dan Wharton. At the end of a week of research, Alcosser and Wharton would spend an afternoon reviewing her finds for the week and narrowing the selection further. The poets that made Alcosser’s final cut were those who were more than great writers; she sought poets whose work had shown a commitment to the natural world. Wharton had his own criteria for the poetry. He eliminated poems that were biologically incorrect. Although the final selection included some whimsical choices, Wharton ensured that the poems were generally accurate and good choices for the zoo audience.

Alcosser had some ideas for poets who could be represented, such as New York Modernist poet Marianne Moore who was famous for her time spent at the zoo. But it took several attempts to find a suitable work among Moore’s tricky writings. Other times Alcosser hit upon a poem and her research led her to discover just how suitable the author was. She knew of Birago Diop, a francophone poet and storyteller from Senegal. She didn’t know that he was also a dedicated veterinarian.

To present the final poems in the best light, Alcosser and Wharton worked with the zoo’s exhibits and graphic artists. Planning the placement, the fonts, and the medium for the signage was a wholly separate and significant creative process. The artists responded to the challenge with great creativity, segmenting longer poems across benches and around an area with circular rafters, so that the poems drew visitors through the spaces.

One excerpt they used from Maurice Sendak is popular with children:

That very night in Max’s Room a forest grew

and grew—

and grew until his ceiling hung with vines

and the walls became the world all around

From Where the Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak, (America, 1914-1993)

The poem’s lines, each on a consecutive stair step, describe the feeling visitors have entering the rainforest exhibit surrounded by its lush vegetation.

Before committing to the expense of engraving stone or ordering signs, the zoo tested some of its poetry presentation ideas with a pilot run. It was a very valuable step that enabled the zoo to avoid missteps and learn about how many poems would be welcomed by the public.

The final installation was marked with a celebration that brought together the Poets House, Alcosser, and a few of the living poets whose work was featured. Native American storyteller and poet Joe Bruchac read poems about friendship to the earth.

Results

Seventy percent of the visitors read and liked the poetry excerpts, according to a study conducted by an outside evaluator. The study measured visitor response to the poems, whether the poetry increased awareness of conservation issues, and which poetry tactics were most effective. It involved 139 interviews with groups of visitors, taken before and after installation and before and after the individual’s zoo visit.

The poems made an impression on people. Roughly half of the 185 individuals interviewed during the longer, open-ended exit interviews cited specific poems.

The interviews also clearly indicated that the poetry had prompted visitors to ponder conservation ideas during their zoo visits. The poems especially helped visitors think about humans as part of ecosystems. The number of comments about this idea shot up 48 percent after participants viewed the poetry displays. Comments about humans’ role in wildlife stewardship increased by 36 percent.

Community Change

The poet residency project has left its mark on its institutional partners, as well. It continues to shape public programs at the zoo and Poets House. Sandra Alcosser is returning to New York this April, during National Poetry Month, for a presentation at Poets House and a two-week field institute at the Central Park Zoo to help cultivate environmental imagination for poets, naturalists, and writers. For the Earth Day celebration, she will be doing readings and tours of the poems at the zoo. She is looking forward to being again among the wild things at Central Park Zoo.

Resources

Evaluation Report (PDF Format, 236 KB)

Images of the Poet-in-Residence project (PowerPoint Presentation, 3.6 MB)