Blog Posts | March 31, 2020

Share ThisIt Started at the Library: Tom Coburn, Civil Rights Ally and Friend

IMLS Director Crosby Kemper on Love in the Time of Crisis and the Life of Senator Coburn

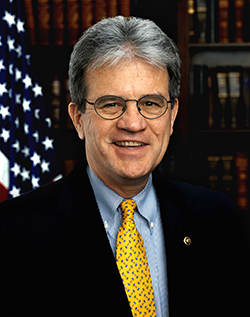

Former Senator Dr. Tom Coburn of Oklahoma died on Saturday. To much of the world, he was known as the most principled fiscal conservative, a.k.a., “Dr. No”, in the United States Senate—a citizen legislator in the old Roman style, who committed to term limits and went home to happily continue to practicing medicine.

At IMLS, he was known as a friend who admired the agency’s fiscal discipline, prudent management, and commitment to professional integrity.

My personal history with Tom Coburn involves the Kansas City Public Library and a civil rights hero named Alvin Sykes.

Alvin is a musician who grew up in Kansas City, Kansas, public housing with an eighth grade education. He often says his real education was in the public libraries of Kansas City, Kansas and Kansas City, Missouri, where his mother brought him when he was very young.

When a friend of his, musician Steve Harvey, was killed in a hate crime at the Liberty Memorial in Kansas City, and his killer was acquitted by an all-white jury, Alvin went to the library. With the help of a reference librarian, he researched recent civil rights legislation, which allowed a charge of violation of civil rights to be a solution to this profound injustice.

With help from an assistant attorney general named Antonin Scalia and a trial attorney in the Justice Department named Richard Roberts, later Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, he initiated a successful campaign to prosecute the killer who remains in jail 30 years later.

This led to Alvin’s career as a civil rights warrior digging into older cases with biased outcomes. This included the murder of Emmett Till, one of the great miscarriages of justice in American history. Alvin befriended the Till family, working with them to create the Emmett Till Bill in Congress and forming the Cold Case Section of the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department. Alvin spent time in Washington organizing majority support on both sides of the aisle.

And here Tom Coburn enters our story. Senator Coburn was a principled enforcer of congressional rules then in effect that new programs needed to be funded by money from reductions elsewhere or the discovery of new money. None was in sight, and Senator Coburn wouldn’t budge on the principle.

But Alvin wouldn’t quit. He called. He wrote. He hung out in the Senator’s office. A lot. Finally, admiring his persistence, Senator Coburn surrendered to a meeting.

Here is Tom Coburn on the Senate Floor after the Till Bill passed and the Cold Case Section of the Civil Rights Division became a reality:

I wanted to tell you something about America with this bill, and it has to do with Alvin Sykes. If you met him, you would immediately fall in love with him.

He is poor as a church mouse. He has led this group with integrity. He has been an honest broker. He has not played the first political game with anybody in Washington. As a matter of fact, he has had games played on him and he has been manipulated. But the fact remains: he has held true to his beliefs and his commitment to the mother of Emmett Till. And because of that, we are going to see this bill come to fruition.

I think that speaks so well of our country, that one person truly made a difference. I cannot say enough about Tom’s stamina, his integrity, his forthrightness, and his determination.

A conservative Senator singularly responsible for the passage of a civil rights bill talking about his love for a poor African-American Buddhist with an eighth grade education is quite something. So the Kansas City Public Library invited Senator Coburn and Alvin Sykes to come for a conversation. The words “truth” and “love” and “integrity” were spoken often and beautifully that night. It was a revelation of two men who had found themselves on the top of a very high ladder together, and both a little closer to justice and to God than most of us will ever be.

There was an audience of about 300 in the library that night, and if there was a dry eye, there I couldn’t see it through my tears.

Three weekends ago, I was at attending a performance of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor in Kansas City—its last before the close of the season due to coronavirus, as is the case for so many other organizations. The lead in the opera was Tom Coburn’s talented, beautiful daughter Sarah. Just before the performance, she told my wife and me that Tom was in hospice.

As I listened to Donizetti’s heartbreaking melodies, I remembered Tom. I thought what he said about our mutual friend Alvin will be said about him: he made us feel better about America, you don’t have to always agree with a man to admire him for integrity and sticking to his principles, and it takes courage and determination and forthrightness to talk about love on the floor of the Senate.

It inspires love in a time of crisis to think of these two great Americans finding justice through the loving recognition of truth in each other.

About the Author

Crosby Kemper III was confirmed by the Senate in January 2020 as the director of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.